When trying to improve alignment in an organisation, our actions are based on less than complete or perfect knowledge about the situation. The better informed we are, the better the chances that we will take the right steps. So learning, in the sense of gathering information and knowledge about a situation, is critical to improving strategic alignment. From this perspective, we need to learn about the parts of the organisation we need to work with, such as strategy, processes, structures, reward systems and so on. We need to know the extent to which these parts in our particular situation are aligned and exactly where the misalignment is. We need to be able to foresee the improvement in alignment that our actions are likely to bring. We also need to be prepared for unforeseen results. Finally, once we act we need to observe the outcomes to see if they are the results we expected.

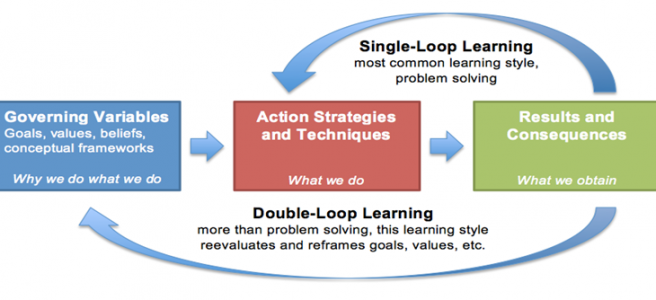

A person can become good at gathering such information and knowledge and using it to find what to do to improve their competence. Once they have done this for a while and become really good at it, we deem them expert. This kind of learning can take time and a commonly cited rule of thumb is that it takes 10,000 hours to become an expert in a certain area. It is important to recognise that not all that is learnt can be articulated, because we may be unaware of much of just how much we have learnt. Argyris and Putnam called this ‘single-loop learning’.

Let’s consider another example of single-loop learning. Someone starting as an accountant might first learn how to code an accounting transaction. Over a period of time this person may become familiar with a broader and more complicated set of transactions, how these transactions are aggregated and grouped together to meet legal reporting requirements and so on. They may also learn about the grey areas where they have the flexibility to represent the situation to the advantage of the company.

This form of learning generally involves individuals working on their own or possibly with others, but following a certain established pattern of activities. The competence they develop can help deal with simple situations as well as complicated ones such as those involved in air-traffic control. It can also help deal with complex adaptive systems such as those involved in baking artisanal bread or diagnosing an illness in a patient. But typical organisational situations are not just complicated and complex. They also involve human beings and each person sees the world a little differently and has their own particular agenda. As members of the group, just as others have different perspectives and goals, we each have our own – and we aren’t necessarily aware of these perspectives and intent.

These mental frames and intent have been developed over a period of time as we have learnt from experience. We remain unaware of a large part of our mental frames and intent because we don’t want to waste time thinking about them. This works well most of the time, but often our subconscious perceptual filters and intent can distort reality in damaging ways. The well-known confirmation bias is what happens when we see only what we want to see, i.e. when our intent shapes our perception. Sometimes, when we interact with someone else, we are able to notice that they are looking at things differently and use this information to adjust our perceptions. For example we might learn from a conversation with someone that we have a bias against someone with a background different from ours.

Argyris and Shon called this ‘double-loop learning’, where we reflect on our assumptions and make corrections where necessary. But this doesn’t happen very often. What we typically do is to pretend, not only to others but also to ourselves, that we don’t actually have a bias. Argyris called this our ‘espoused theory’ because if someone were to ask about it, we would insist we don’t have the bias. But since most our behaviour is unconscious, it is possible that our actions do demonstrate the bias. Argyris called this our ‘theory in action’. Everyone has some gaps between their espoused theory and theory in action. Each of us has gaps of varying degrees and in different areas.

It is not only individuals that have perceptual filters that distort reality. Groups can share perceptual filters resulting in ‘group-think’ or tune out certain topics that are so uncomfortable that they remain undiscussed, i.e. elephants in the room. Resistance to discussing such topics can be strong and it is possible that individuals who ignore the taboo are punished for transgressing.

So what does this have to do with alignment? If we restrict ourselves to single-loop learning when considering actions to address misalignment, the unarticulated assumptions, biases and topics that are excluded from the conversation are likely to remain in place. Because of this, the changes we make are less likely to be successful and if they are, less likely to be sustained.

Next week we’ll look at another form of learning that enables us to harness diversity of thinking.

If you are interested in learning more about organisational alignment, how misalignment can arise and what you can do about it join the community. Along the way, I’ll share some tools and frameworks that might help you improve alignment in your organisation.